Journalism/ Political Science Malo periculosam libertatem quam quietem servitium.

PANDEMIC VACCINES AS A GLOBAL PUBLIC GOOD: THE CASE OF COVAX

ABSTRACT

The outbreak and spread of pandemics are becoming a global challenge that directly tests the ability of global health governance mechanisms to function. The unknown nature of new viruses creates uncertainty in global health governance (Abeysinghe 2019, 11-12.). What we are experiencing with COVID-19, namely due to the highly infectious nature of the virus and the free movement of people, will remain a global problem as long as one country does not survive the crisis. The development and distribution of vaccines are essential to prevent the escalation of this global public health crisis and ultimately address such challenges. While the World Health Organization (WHO) has made it clear that making vaccines a public good is a matter of equity and fairness, any COVID-19 vaccine should be a global public good (Ellyatt 2020). However, since the outbreak, there have been differing views on the nature of the COVID-19 vaccine among sovereign countries and international organizations.

This paper argues that global international bodies, particularly health agencies, need to work together to reach a consensus on making the COVID-19 vaccine a global public good. It will promote cross-national collaboration between vaccine developers and manufacturers, share knowledge and information, and help accelerate vaccine development, improve vaccine efficacy and maximize vaccine production. Currently, the COVAX initiative has the potential to contribute to this goal. This paper describes the current strengths and challenges of the initiative. Finally, based on the existing institutional framework, it suggests areas and recommendations for refining COVAX.

EFFORTS OF THE GLOBAL PROJECTS ON VACCINES

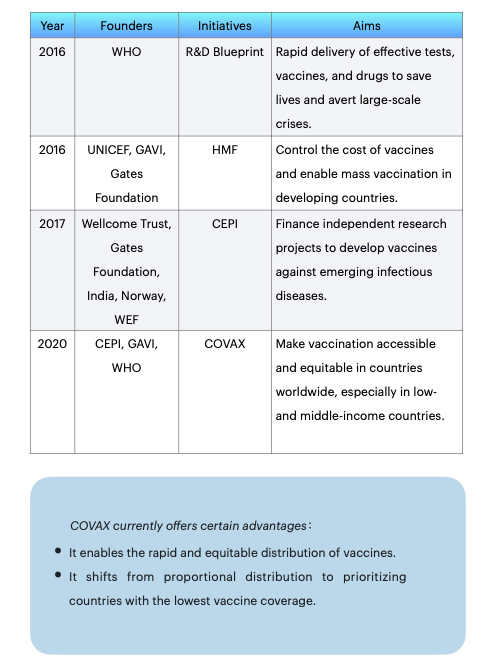

Global health governance has a consensus that vaccines are essential for preventing and controlling infectious diseases. Before COVAX, there have been several projects and foundations that have worked towards this end.

In 2016, WHO created the R&D Blueprint for research and development. It sets global standards for clinical trials of vaccines during pandemics and provides priority directions and pathways for research and development efforts ("Background to the WHO R&D Blueprint Pathogens" 2016). In the same year, UNICEF, together with the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization and the Gates Foundation, created the Healthy Markets Framework (HMF), which aims to control the cost of vaccines and enable mass vaccination in developing countries ('Healthy Markets Framework' 2016). In 2017, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI) was established. Following a new outbreak, nine vaccine research and development projects were funded, investing nearly US$750 million and requiring that research findings be made available globally rather than only to individual countries to ensure equitable access to vaccines at source (Gouglas et al., 2019).

In response to this COVID-19, the COVAX initiative was established in March 2020. COVAX provides advance market commitments (AMCs) to pharmaceutical companies on behalf of each country. Wealthy countries provide funding in advance of vaccine development, gain priority access to vaccines and consolidate demand for vaccines at lower prices (Berkley 2020).

DILEMMAS OF COVAX

Although COVAX has accelerated vaccine development by coordinating the global supply chain, its current initiatives are short-term measures that do not meet the vaccine supply situation in the long term. Meanwhile, the effective implementation of COVAX faces multiple practical dilemmas in terms of financing, delivery, and population perception, which are also linked to the new characteristics of the COVID-19 vaccine itself. This section mainly addresses the current issues of COVAX.

1. INFLEXIBLE SYSTEM DESIGN WITH NO BINDING PROVISIONS

The major dilemma encountered by COVAX comes primarily from the design of the system, which needs more flexibility in the complexities of an evolving pandemic. None of the current global health governance systems has a rigid regulatory and response mechanism. It can only advocate and encourage the international community to cooperate as much as possible. However, competition has now developed between the leading suppliers of vaccines. A disruption in capacity in India, for example, its primary source of vaccine production, would create a vulnerable situation (Das 2021). Added to this is the rush by rich countries and the uncertainty of vaccine demand in other countries.

2. TRADITIONAL FINANCING METHODS AND EXCESSIVE RELIANCE ON DEVELOPED NATIONS

COVAX has adopted the traditional aid financing approach, which has left low-income countries entirely at the mercy of rich nations and profit-driven companies. As a result, major pharmaceutical companies have generated huge revenues by selling most of their vaccines to the financially strong governments of North America and Europe.

More than 90 high-income countries worldwide invest in the COVAX Fund as self-financing Participants (SFPs), and 92 low-income countries are eligible for COVAX vaccine assistance ("92 Low- and Middle-Income Economies Eligible to Get Access to COVID-19 Vaccines through Gavi COVAX AMC" 2020). As long as the vaccine developed is deemed safe and effective, it is theoretically available to both wealthy and developing countries that are members of COVAX. Wealthy countries contribute to the COVAX mechanism by investing funds to obtain a vaccine that protects a certain percentage of the population. The vaccine is available to about 20% of the population in poorer countries (Kenny 2021). It means that only if enough wealthy countries invest in the vaccine will COVAX have the money to help developing countries.

3. TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT RELIES ON A FEW NATIONS ANDPHARMACEUTICALFIRMS

From a technical point of view, the barriers to entry for developing the COVID-19 vaccine are high. The vaccine giants currently dominate the majority of the global vaccine market, and the development and production of the COVID-19 vaccine are concentrated in a few major pharmaceutical companies. The leading technology for the COVID-19 vaccine is focused on a few countries, with the core science and technology still relying on the scientific strength of high-income countries themselves. It has resulted in the continued dependence of low-income countries on high-income countries and pharmaceutical companies. The number of countries with the capacity and willingness to supply vaccines is minimal. Because the vaccine industry is highly capital-intensive and has a high technological threshold, vaccine supply is now highly exclusive. As a result, a vast "vaccine gap" has been created between developed and developing countries.

4. INEFFICIENTANDLOW-MATCHINGDISTRIBUTION

The distribution of COVID-19 vaccines has now shifted from undersupply to inefficient supply-demand matches. At the start of the pandemic, the scale of vaccine production needed to be revised to meet its huge demand, and contracts with vaccine manufacturers in high-income countries crowded out stocks, making it impossible for COVAX to meet its procurement targets. However, as vaccine suppliers increase their production capacity and vaccination rates rise, vaccine production capacity has increased while demand continues to fall. Some vaccines have a shelf life of only six to nine months and require ultra-low temperature storage and transport. The main challenge has changed from an oversupply of vaccines to an inefficient supply-demand match. In some developing countries, the demand side of vaccines is receiving vaccines close to their expiry dates due to geographical distance and storage conditions.

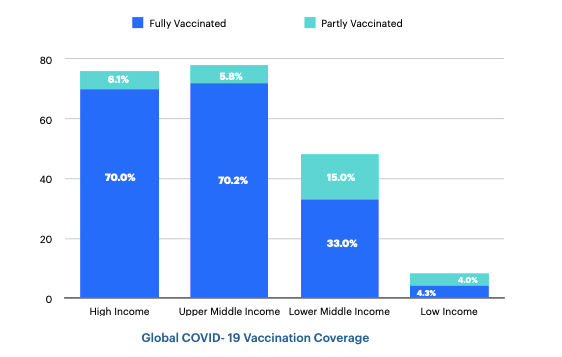

According to the latest data, 68.7% of the world's population has received at least one COVID-19 vaccine. Globally, 13.06 billion doses have been administered. However, in low-income countries, only 25.1% of the population has received at least one dose of the vaccine (Our World in Data 2022). The graph below shows that global vaccination rates differ markedly between high- and low-income countries (Mathieu et al. 2021).

5. VACCINE NATIONALISM STANDS OUT

Furthermore, vaccine nationalism continues to exist globally. It is mainly manifested in the fact that some high-income countries stockpile excessive vaccines within their borders but fail to fulfill their share of donations. Meanwhile, some developing countries face obstacles such as inefficient distribution and a hesitant population to accept vaccines. These are obstacles to the timely and effective roll-out of vaccination.

Theoretically, a paradox emerges in that the most important beneficiaries and demand for vaccines are often developing countries that cannot afford to support vaccine development and production. Not only do these countries generate more free-rider behavior, but weaker domestic governance capacity makes it difficult to achieve universal access to the vaccines they supply.

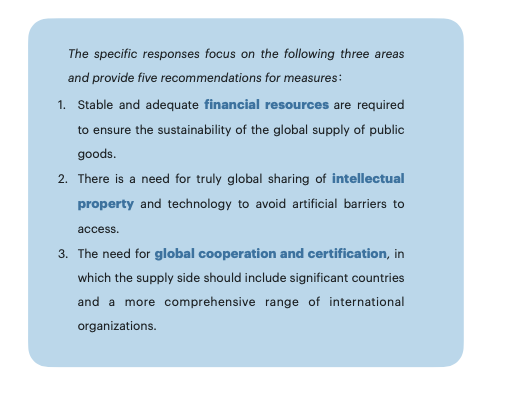

COVAX faces problems mainly regarding system setup, financing methods, technology patents, and vaccine distribution. Although the

need for vaccine resource assistance is concentrated in the poorer developing countries, the participating sectors should be more comprehensive regarding the global public goods supply. This paper proposes that, based on the current COVAX, the COVID-19 vaccine could be public, cooperative, and sustainable.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. CREATE A FRAMEWORK CONVENTION AND MODIFY EXISTING FUNDING METHODS

A framework convention can be an opportunity to close the international response gap, clarify responsibilities between countries and organizations, and establish and strengthen legal obligations and norms. COVAX is now critically in need of reform to reduce its dependence on financing from wealthy countries. The cost of developing and producing new vaccines is high and requires large amounts of financial support. More attention must be paid to self-financing participants while encouraging national investment and combining autonomous contributions and support for international mechanisms to raise funds. Although COVAX relies strongly on funding from developed countries, national actors still need more leadership. Moreover, the establishment of a competitive mechanism will provide more incentives for national actors to get involved.

In addition to national investments, new financing is to be supported by enhanced joint work with financial institutions and organizations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the WTO. The World Bank, an important source of funding for global health governance, has created flexible financial instruments specifically to raise and use the funds needed for research and development of a new vaccine for COVID-19 ("COVAX and World Bank to Accelerate Vaccine Access for Developing Countries" 2021). At the same time, financial institutions need to be called upon to provide additional funding for low- and middle-income countries through substantial grants and concessional funding and encourage financial support from international financial institutions, regional development banks, and other public and private financing organizations.

The International Finance Facility for Immunization (IFFIm) is a successful example that COVAX can refer to for financing innovative vaccines. It issues 'vaccine bonds' to investors based mainly in developed economies, mobilizing funds to provide vaccinations to developing economies with secondary support from government donors. IFFIm has achieved some of the claims made in its aid commitments and has significantly contributed to global health. Although there are and have been more problems, alternative models of vaccine financing are possible (Hughes-McLure and Mawdsley 2022).

Continue to seek greater involvement of non-governmental foundations in raising funds for developing new vaccines. For instance, private foundations such as the Gates Foundation and private biotechnology companies such as Ology Bio-services and Bharat Biotech, India, could explore new models for funding vaccine research and development. In this context, international professional bodies must be established or appointed to oversee and coordinate the established funds.

2. MONITOR IP SHARE TRANSFER AND SETUP OF MRNA VACCINE CENTERS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

The resources required for a sustained supply and effective distribution of vaccines cannot be afforded by COVAX alone. The sharing of proprietary vaccine technologies, the free export of essential vaccine manufacturing materials, and international vaccine certification are all critical. In globalization, a refined division of labor between countries working together will help drive the vaccine production supply chain. A global supply chain would be an essential safeguard to maintain its enforceability. COVAX has to urge WTO members to accelerate negotiations to help them find a practical solution to intellectual property rights (IPRs).

The U.S. announced in May last year that it would drop patent protection for vaccine-related intellectual property (Macias, Breuninger, and Franck 2021). More developing countries could break through patent restrictions and expand vaccine production. As a result, they are increasing the global supply of vaccines and reducing the 'vaccine divide' between developed and developing countries. However, waiving the relevant IPR patent protection does not directly enhance the technology for mass production in developing countries. Patent waivers will only significantly impact if vaccine manufacturers share their manufacturing methods through technology transfer. MRNA Vaccine Technology Transfer Centre was established in South Africa in June 2021 ("WHO Announces First Technology Recipients of MRNA Vaccine Hub with Strong Support from African and European Partners" 2022). It sets the stage for the local production of mRNA vaccines. However, the center is underfunded and has a long research and development cycle.

Drawing on such cases, mobilize assistance from developed countries to establish mRNA vaccines and other vaccine centers and build production capacity in Africa, Latin America, and other low- and middle-income regions as soon as possible. Even without guaranteed financial investment from developed countries, COVAX can establish channels for technology exchange, involving R&D companies in vaccine centers and facilitating vaccine technology transfer and local production.

3. JOINT INTERNATIONAL HEALTH ORGANIZATIONS TO ACCELERATE VACCINE CERTIFICATION SYSTEM

While the COVAX project focuses on purchase and distribution, multiple steps to promote mutual recognition and uniformity of vaccine technologies and quality standards remain fundamental. There are multiple technical routes to vaccine development. How can their effectiveness be evaluated? Can internationally agreed standards for vaccines be developed? Can the regulations for vaccines be mutually accepted by national drug regulators?

Promote alliances with WHO, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and other professional health bodies to establish accreditation systems for professional bodies and to include more vaccines in their accreditation systems as soon as possible. Break the dependence on high-income countries and a few pharmaceutical companies, stimulate more locally targeted solutions, promote lower prices for vaccines and medicines, and invest in local capacity in low- and middle-income countries. While the COVAX program is being implemented in participating countries, it is also essential to encourage low and middle-income countries to continue to develop vaccines independently rather than relying exclusively on COVAX to purchase distribution and invest in their manufacturing capacity.

4. BUILDATRANSPARENTANDEFFECTIVESYSTEMOF VACCINE EXCHANGE MECHANISMS

The term "vaccine nationalism" describes countries, mainly developed countries, that keep large doses for their populations, thus limiting vaccines to low-income economies and seriously affecting the distribution of supply and demand in COVAX.

There is an ongoing need for greater transparency of national vaccine stockpile data. GAVI is currently exploring a project for countries to exchange vaccine doses. COVAX, in collaboration with GAVI to create and improve this exchange mechanism, needs to be committed. Now, exchanges are more limited to direct country-to-country dialogue, such as the agreement between Israel and South Korea in August 2021 to send some vaccines that were about to expire to South Korea (Smith and Williams 2021). However, inter-regional or more systematic, transparent, and effective mechanisms must be urgently improved.

5. ASSIST DEVELOPING COUNTRIES WITH LOCAL VACCINATION CAMPAIGNS

Finally, COVAX overlooks the differences in vaccination capacity between countries, and some economically disadvantaged countries cannot vaccinate on a large scale. COVAX needs to join forces with nations that vaccinate efficiently and with organizations with experience building teams for follow-up vaccination. In addition, it will help local governments to launch vaccination campaigns, including establishing data systems, educating to combat 'vaccine hesitancy,' building vaccine confidence, etc.

CONCLUSIONS

Modifying market instruments in pandemics may be appropriate, as profit motives and the organizational capacity of the pharmaceutical industry remain a powerful way to respond to future global health crises. However, the broader context of the international setting remains one of inequality between countries. Such disparities necessitate public research and development funding through global health governance mechanisms and significant procurement commitments.

Equitable access to vaccines on a global scale is essential for COVAX to fight future variants and diseases. COVAX now requires urgent changes in innovation financing, intellectual property sharing, vaccine certification, and effective distribution systems. More importantly, it must join efforts with more experienced international organizational actors, high- and low-income countries, and multinational pharmaceutical companies. A long-term vaccine production system that achieves the primary goal of global vaccine equity and efficacy while maintaining incentives for developing life-saving medical technologies. Intellectual property and patent law must evolve to acknowledge the global health crisis and provide the legal framework for vaccines to be recognized as a global public good.

Bibliography

“92 Low- and Middle-Income Economies Eligible to Get Access to COVID-19 Vaccines through Gavi COVAX AMC.” 2020. Www.gavi.org. July 21, 2020. https:// www.gavi.org/news/media-room/92-low-middle-income-economies-eligible- access-covid-19-vaccines-gavi-covax-amc.

Abeysinghe, Sudeepa. 2019. Pandemics, Publics, and Politics: Staging Responses to Public Health Crises. Edited by Benedicte Carlsen and Kristian Bjørkdahl. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

“Background to the WHO R&D Blueprint Pathogens.” 2016. Www.who.int. 2016. https:// www.who.int/observatories/global-observatory-on-health-research-and- development/analyses-and-syntheses/who-r-d-blueprint/background.

Berkley, Seth. 2020. “COVAX Explained.” Www.gavi.org. September 3, 2020. https:// www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/covax-explained.

“COVAX and World Bank to Accelerate Vaccine Access for Developing Countries.” 2021. World Bank. July 26, 2021. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press- release/2021/07/26/covax-and-world-bank-to-accelerate-vaccine-access-for- developing-countries.

Das, Krishna N. 2021. “India Delays COVID-19 Vaccine Supplies to WHO-Backed COVAX, Sources Say.” Reuters, October 20, 2021, sec. India. https:// www.reuters.com/world/india/india-delays-covid-19-vaccine-supplies-who- backed-covax-sources-say-2021-10-19/.

Elder, Kate, and Jessica Malter. 2022. “COVAX: A Broken Promise for Vaccine Equity.” Doctors without Borders - USA. February 21, 2022. https:// www.doctorswithoutborders.org/latest/covax-broken-promise-vaccine-equity.

Ellyatt, Holly. 2020. “Covid Vaccines Must Be ‘a Global, Public Good,’ WHO Says.” CNBC. November 19, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/19/coronavirus- vaccines-must-be-a-global-public-good-who-says.html.

Gouglas, Dimitrios, Mario Christodoulou, Stanley A Plotkin, and Richard Hatchett. 2019. “CEPI: Driving Progress toward Epidemic Preparedness and Response.” Epidemiologic Reviews 41 (1): 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxz012.

“Healthy Markets Framework.” 2016. Gavi. https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/ document/healthy-markets-framework--public-overviewpdf.pdf.

Hein, Wolfgang, and Anne Paschke. 2020. Access to COVID-19 Vaccines and Medicines - a Global Public Good. SSOAR. Vol. 4. Hamburg: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies - Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien.

https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/68332.

Hughes-McLure, Sarah, and Emma Mawdsley. 2022. “Innovative Finance for Development? Vaccine Bonds and the Hidden Costs of Financialization.” Economic Geography 98 (2): 145–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.2020090.

Kaul, Inge, Isabelle Grunberg, and Marc A Stern. 2016. Global Public Goods:

International Cooperation in the 21st Century. New York; Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Kenny, Peter. 2021. “COVAX Eyes Vaccines for Only 20% of People in Poorer Nations

This Year.” Www.aa.com.tr. September 9, 2021. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/ latest-on-coronavirus-outbreak/covax-eyes-vaccines-for-only-20-of-people-in- poorer-nations-this-year/2359665.

Macias, Amanda, Kevin Breuninger, and Thomas Franck. 2021. “U.S. Backs Waiving Patent Protections for Covid Vaccines, Citing Global Health Crisis.” CNBC. May 5, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/05/us-backs-covid-vaccine- intellectual-property-waivers-to-expand-access-to-shots-worldwide.html.

Mathieu, Edouard, Hannah Ritchie, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Max Roser, Joe Hasell, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, and Lucas Rodés-Guirao. 2021. “A Global Database of COVID-19 Vaccinations.” Nature Human Behaviour H5 (May). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8.

Our World in Data. 2022. “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations - Statistics and Research.” Our World in Data. 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/covid- vaccinations.

Smith, Josh, and Dan Williams. 2021. “S. Korea Is to Get 700,000 COVID-19 Vaccines Doses from Israel.” Reuters, July 6, 2021, sec. Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/israel-south- korea-agree-covid-19-vaccine-exchange-report-2021-07-06/.

“Vaccines Supply Annual Report.” 2016. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/supply/media/ %20166/file/UNICEF-supply-division-annual-report-2016.pdf.

WHO. 2020. “COVAX: Working for Global Equitable Access to COVID-19 Vaccines.” World Health Organization. 2020. https://www.who.int/initiatives/act- accelerator/covax.

“WHO Announces First Technology Recipients of MRNA Vaccine Hub with Strong Support from African and European Partners.” 2022. Www.who.int. WHO. February 18, 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/18-02-2022-who- announces-first-technology-recipients-of-mrna-vaccine-hub-with-strong- support-from-african-and-european-partners.

喜欢我的文章吗?

别忘了给点支持与赞赏,让我知道创作的路上有你陪伴。

发布评论…